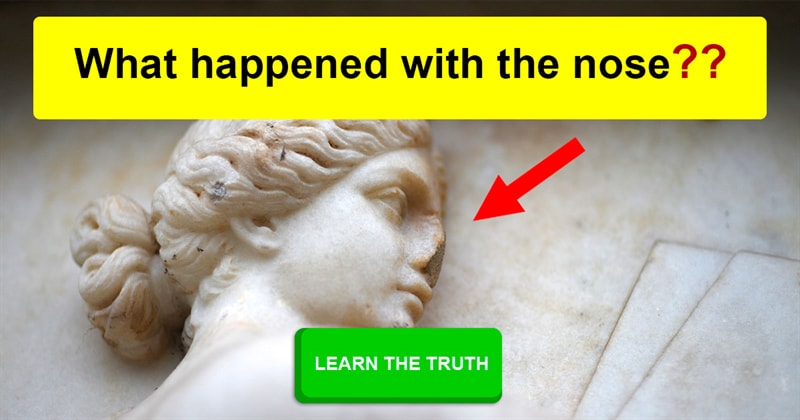

Why have the noses been knocked off so many ancient sculptures?

This is a question that a lot of people have asked. If you have ever visited a museum, you have probably seen ancient sculptures such as this one, a Greek marble head of the poetess Sappho currently held in the Glyptothek in Munich, with a missing nose:

A smashed or missing nose is a common feature on ancient sculptures from all ancient cultures and all time periods of ancient history. It is by no means a feature that is confined to sculptures of any particular culture or era. Even the nose on the Great Sphinx, which stands on the Giza Plateau in Egypt alongside the great pyramids, is famously missing:

If you have seen one of these sculptures, you have probably wondered “What happened to the nose?” Some people seem to have a false impression that the noses on the majority of these sculptures were deliberately removed by someone.

It is true that a few ancient sculptures were indeed deliberately defaced by various peoples at various times for various different reasons. For instance, here is a first-century AD Greek marble head of the goddess Aphrodite that was discovered in the Athenian Agora. You can tell that this particular marble head was at some point deliberately vandalized by Christians because they chiseled a cross into the goddess’s forehead:

This marble head, however, is an exceptional case that is not representative of the majority of ancient sculptures that are missing noses. For the vast majority of ancient sculptures that are missing noses, the reason for the missing nose has nothing to do with people at all. Instead, the reason for the missing nose simply has to do with the natural wear that the sculpture has suffered over time.

The fact is, ancient sculptures are thousands of years old and they have all undergone considerable natural wear over time. The statues we see in museums today are almost always beaten, battered, and damaged by time and exposure to the elements. Parts of sculptures that stick out, such as noses, arms, heads, and other appendages are almost always the first parts to break off. Other parts that are more securely attached, such as legs and torsos, are generally more likely to remain intact.

You are probably familiar with the ancient Greek statue shown below. It was found on the Greek island of Melos and was originally sculpted by Alexandros of Antioch in around the late second century BC. It is known as the Aphrodite of Melos or, more commonly, Venus de Milo. It famously has no arms:

Once upon a time, the Aphrodite of Melos did, in fact, have arms, but they broke off at some point, as arms, noses, and legs often tend to do. The exact same thing has happened to many other sculptures’ noses. Because the noses stick out, they tend to break off easily.

Greek sculptures as we see them today are merely worn-out husks of their former glory. They were originally brightly painted, but most of the original pigments long ago faded or flaked off, leaving the bare, white marble exposed. Some exceptionally well-preserved sculptures do still retain traces of their original coloration, though. For example:

ABOVE: Well-preserved Hellenistic Greek sculpture from Tanagra depicting a well-dressed woman carrying a fan and wearing a sun hat, dating to c. 330 – c. 325 BC, still retaining visible traces of its original pigment

ABOVE: Well-preserved Boiotian terra-cotta sculpture of a man carrying a ram, dating to the mid-fifth century BC

Even for the sculptures that do not retain visible color to the naked eye, archaeologists can detect traces of pigment under an ultraviolet light using special techniques. There are also dozens of references to painted sculptures in ancient Greek literature as well, such as in Euripides's Helen, in which Helen laments (in translation, of course):

“My life and fortunes are a monstrosity,

Partly because of Hera, partly because of my beauty.

If only I could shed my beauty and assume an uglier aspect

The way you would wipe color off a statue.”

However, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, classical scholars and art historians tacitly denied that Greek sculptures were originally painted, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, because, perhaps influenced by contemporary racialist ideology, they believed that “white is beautiful” and that the whiter something is, the more beautiful it is.

This may sound ridiculous to us today, but, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the firm conviction that ancient Greek sculptures must have originally been pure white led the curators of the British Museum to scrape off the surfaces of many of the ancient Greek sculptures in their collection, including the Elgin Marbles, using tools which included scrapers and chisels. Parian marble, the kind of marble that the Elgin Marbles are carved from, naturally turns a light cream color when exposed to air. That is the color that the Elgin Marbles were when they arrived in Britain.

The British Museum, however, was so convinced that the sculptures must have originally been white that they scraped off most of the cream-colored surface of many of the sculptures. You can imagine how horrified the curators would have been had they been informed that, not only was the cream color natural, but that the sculptures they were “cleaning” had originally been painted. In the late twentieth century, scholars finally began to open up to the fact that classical sculptures were originally painted and this fact is now widely accepted, albeit only begrudgingly by many, who prefer the sculptures in their current lily-white state.

Many Greek sculptures were also originally holding objects made of precious metals, such as scepters or weapons. These were almost invariably stripped away from the statues long ago, during times of economic hardship when such metals were needed to fuel the economy. Towards the end of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), the Athenians stripped the precious metals from their own Acropolis to fund their war with the Spartans. The Phocians did the same thing to the temple of Apollo at Delphi during the Third Sacred War (356–346 BC). This is the reason why Greek sculptures are often in awkward or unusual poses, because many of them were originally holding things.

Have you ever wondered why ancient sculptures are missing body parts?

Interesting Facts

9 photos that depict history vividly

7/21/2021

by

Della Moon

These captivating historical pictures will definitely leave you stunned!

9 incredibly old and worn out items you will find interesting

7/18/2021

by

Della Moon

There are many worn out items and antiques that people find hideous, which is not the case for the wonderful objects you're going to see in this post.

6 amazing countries where you can live better for cheaper

7/25/2021

by

Della Moon

There are many underrated countries with beautiful views and picturesque cities. Most of them are incredible cheap to live in. Let's learn about 6 such countries.

7 images that depict life from a different point of view

8/11/2021

by

brian l

In today’s post, we would be sharing these seven photos that show life from another perspective.

14 beautiful vintage pictures colorized by a talented artist

8/9/2021

by

Della Moon

This talented artist surely knows how to give new life to old black and white pictures – his works will blow your mind away!